At Hammer & Hand we understand that building – both new construction and renovation – can be a form of climate action.

But what do we mean by “climate action”? Because climate change is driven primarily by the burning of fossil fuels, then climate action has to mean, ultimately, keeping coal, oil, and gas in the ground. How do builders, architects, and building owners do that? By reducing demand for those fossil fuels through energy efficiency, energy conservation, and a shift to renewable energy. As Carbon Tracker Initiative says, fossil fuels demand destruction equals climate security.

There are two lenses through which to view and understand “building as climate action.” Both highlight the role that high performance passive building can play as a powerful lever for climate solution making.

The first lens is focused at the scale of the project site. Can my project be “zero carbon” on a net basis? Can the building generate more energy every year through onsite renewable energy (usually solar PV) than it consumes for heating, cooling, lighting, and plug loads? Over the lifespan of the building can this net surplus offset the “embodied energy” of the construction process and materials? And is the building part of an urban fabric that is walkable, transit-oriented, and bike friendly so that occupants aren’t forced to drive everywhere? If not, is there enough surplus onsite renewable energy generation at my site to power an electric vehicle and still stay “net positive energy” for the year?

Madrona Passive House, shown here during last weekend’s NW Green Home Tour, projected to be certified as a Net Zero Energy Building by the International Living Future Institute. The home’s 9.8 kW solar array generated more energy in April than the home consumed, including the charging of the family’s Nissan Leaf.

This site scale understanding of “building as climate action” has a powerful internal “do no harm” logic to it, hence the growth in net zero energy building certifications from the likes of the International Living Future Institute, Built Green, Earth Advantage, and others. By creating a net zero or net positive energy building you are claiming responsibility for the variables on your site that you can control – building energy performance and onsite renewable energy generation – and maximizing them. The formula is straightforward; start with Passive House to minimize building energy demand and then add a reasonably-sized PV array to generate the onsite energy necessary to reach net positive energy. Given current governmental incentives (plus falling solar PV prices), that PV array can also be a really smart investment, paying for itself in a matter of a few years.

(For more about Passive House plus solar as a means to Net Zero Energy Building, read this two part series.)

The second lens through which to understand “building as climate action” is at a much larger scale: regional, continental, and even global. It starts with the larger view of global greenhouse gas emissions and what factors contribute to their rise or decline.

One or more of the four factors shown on the left of the formula above (called the “Kaya Identity” for the economist Yoichi Kaya who developed it) needs to hit zero if we are to realize zero emissions in the future. We know that population will likely increase to 9 billion in the next few decades. We hope, if we care about economic justice, that GDP per capita will increase around the world as more and more people rise out of poverty. So those first two circles will grow. That puts more pressure on the energy intensity and carbon intensity circles to shrink. By pursuing the revolutionary energy efficiency gains of Passive House, our buildings can play an important role in driving down the energy intensity of the built environment. So our buildings can help shrink that third circle. And if we install onsite renewable energy, regardless of whether it means the building reaches net zero or net positive energy at the site scale, we are helping to make the overall energy mix less carbon intensive, shrinking that fourth circle. Of course, we could decide to use the money that we would otherwise spend on onsite renewables and invest it instead in grid-scale solar or wind power somewhere else in the world that is really sunny or windy. That would shrink that carbon intensity circle even more. Whatever works. The point is that humanity needs to push as hard as possible on reducing both the energy intensity and carbon intensity of the global economy, and both passive building and net positive energy building are powerful tools to do just that.

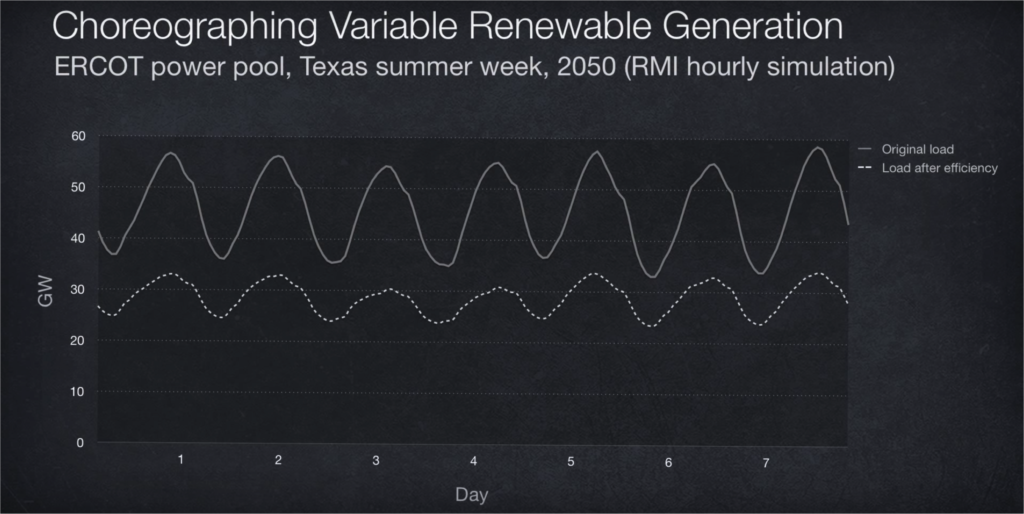

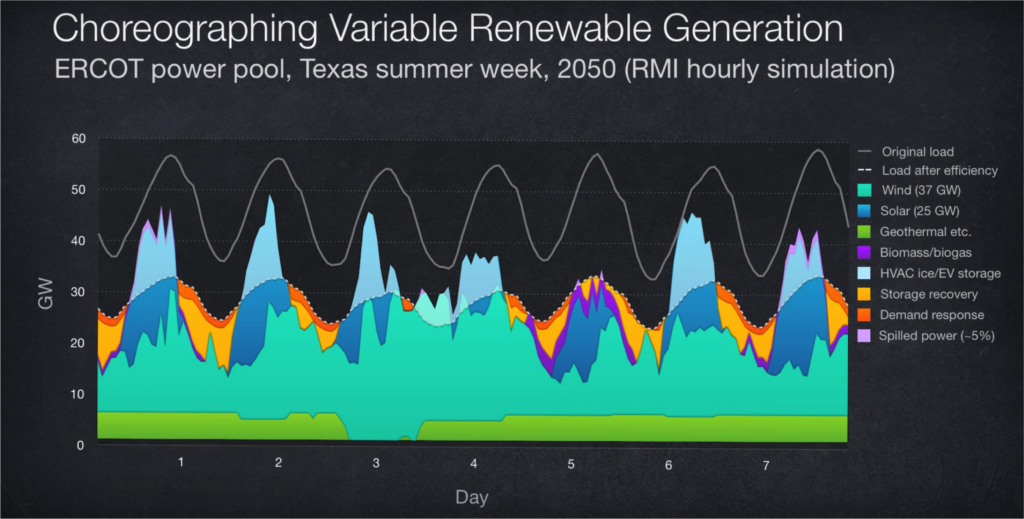

Furthermore, Passive House and Net Zero Energy buildings lay the foundation for a future green energy grid, because their energy efficiency not only reduces overall demand on the grid but also flattens the peaks and valleys of that demand.

As our colleague Graham Irwin points out, über-efficient buildings function as thermal batteries, storing heat (or cool) energy and metering it out over the course of the day with little need for additional inputs of active heating or cooling. This means that at times of the day when heating or cooling energy use from conventional buildings spikes (like in early evening when people get home from work and turn on the heat or the AC), Passive House building energy use remains flat. The flattening effect that this has on the peaks and valleys of grid demand makes it easier to fill in the gaps with a mix of renewables, demand response, and storage.

Building as climate action.

P.S. See Amory Lovins describe how energy efficiency makes the green grid easier to achieve, in his video “The Storage Necessity Myth.”