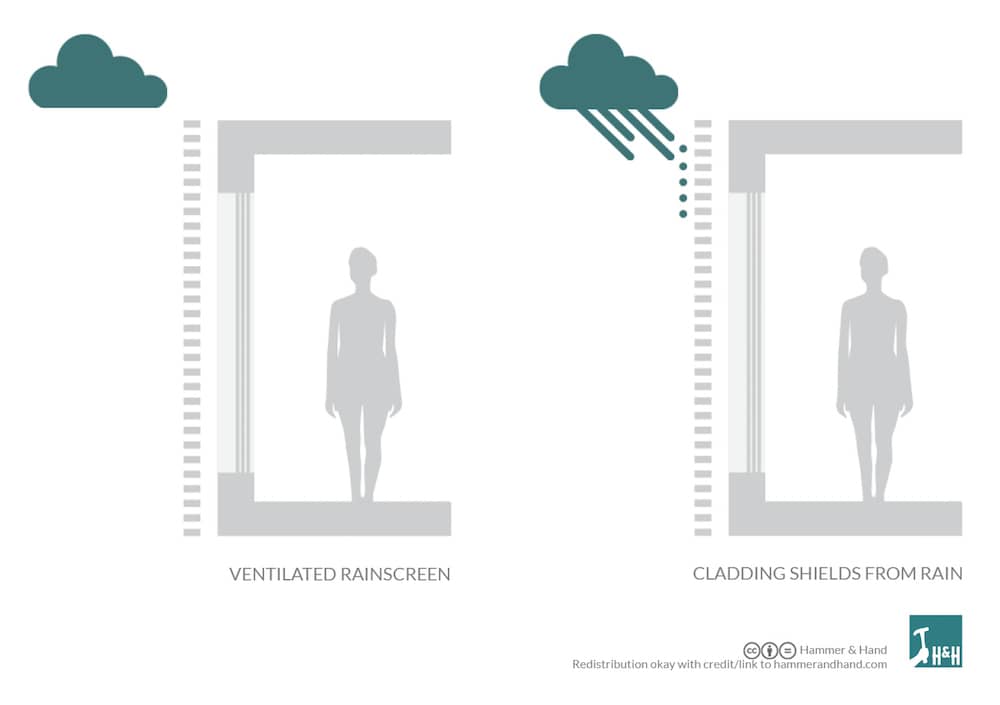

Given their name, it’s no surprise that there’s some confusion about rainscreens and what they do. The “rain” and the “screen” refer to one important function of rainscreens: shielding a building from bulk water intrusion. But the term misses their other critically-important function: helping walls to dry out.

It’s all about “minding the gap.”

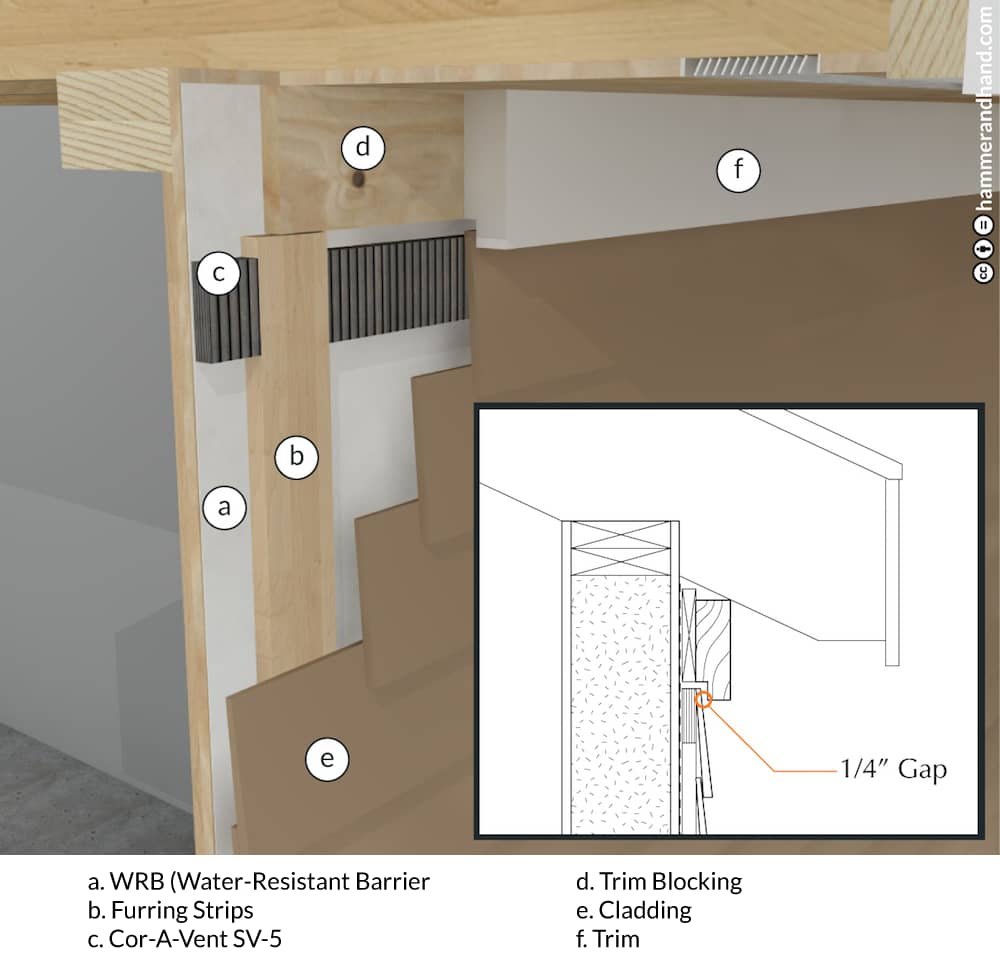

Rainscreens, or ventilated siding, as I prefer to call them, consist of three layers: the cladding, the gap, and the water-resistive barrier (WRB).

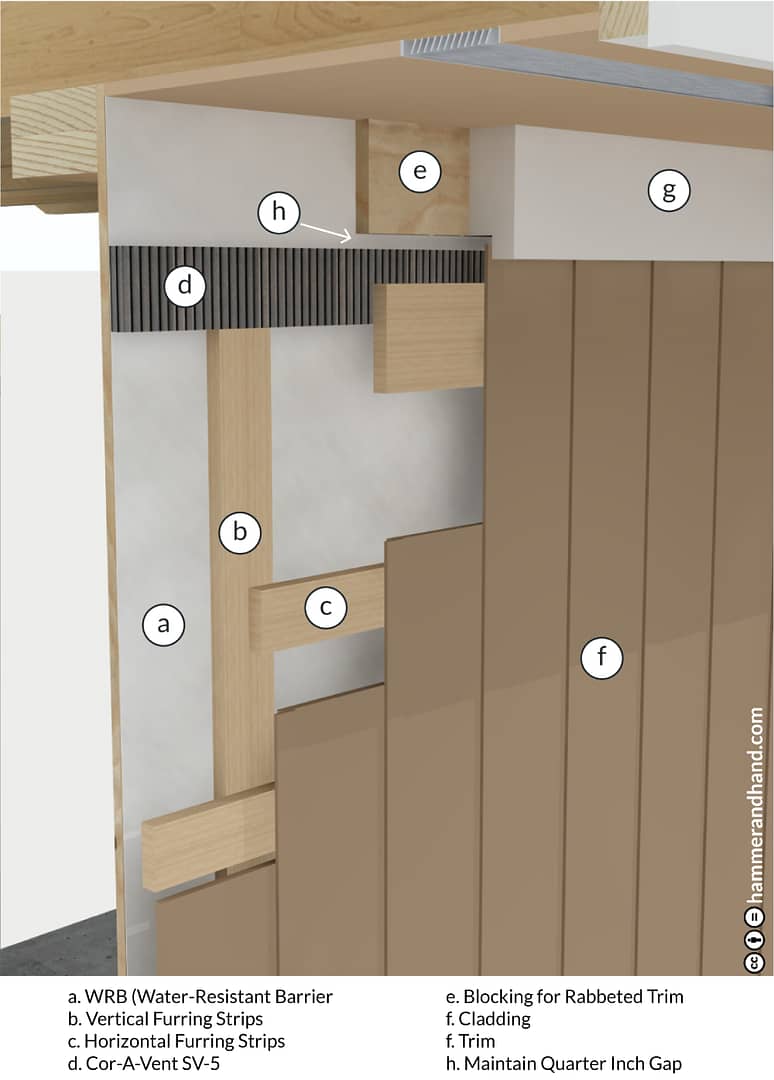

Rainscreen detail from our Best Practices Manual.

The cladding’s job is to protect the WRB from the elements, such as rain and wind.

The WRB’s job (think Typar or Blueskin) is to protect the rest of the building from the elements, especially bulk water (rain) and air intrusion (wind).

When you add a gap between the cladding and the WRB you’ve got yourself a rainscreen. All it takes is a simple batten system. The simplicity of rainscreens belies their power, because that rainscreen cavity is a lifesaving detail for many buildings, especially in our damp, Cascadian climate.

Built properly, this cavity will:

- Introduce a capillary break between the cladding and the WRB, short circuiting the wicking of moisture between the two layers.

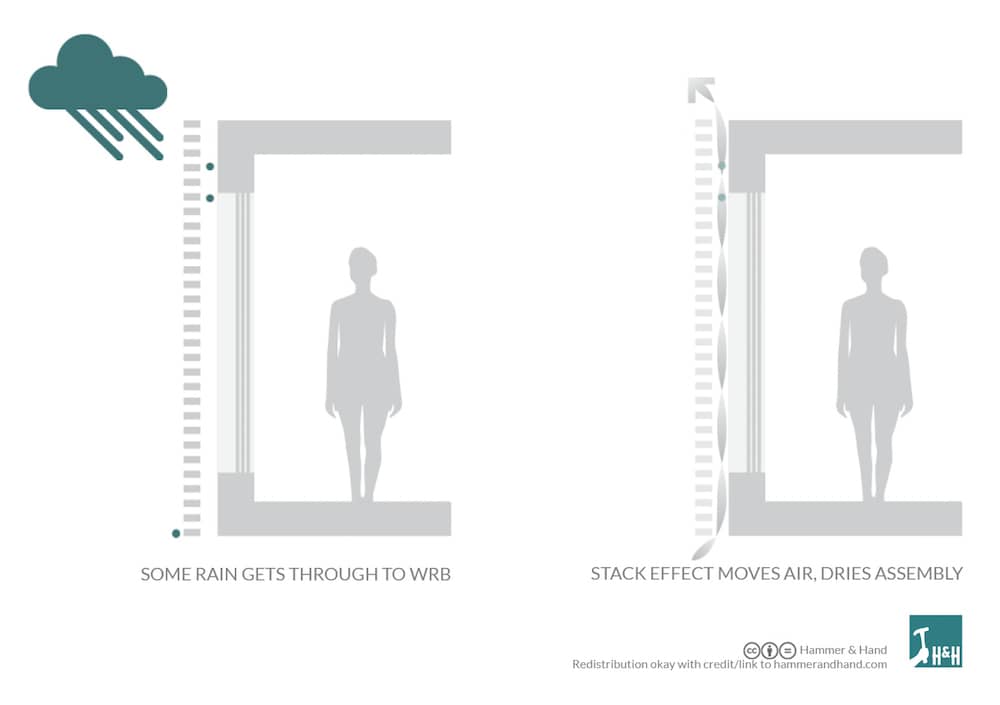

- Create a drainage plane between the two layers, allowing any bulk water that gets through the cladding to drain away harmlessly.

- Generate an air-moving stack effect (when ventilated at top and bottom) that creates hundreds of air changes per hour between the cladding and the WRB.

It should be noted that many rainscreens built today are not ventilated and therefore only serve the capillary break and drainage plane functions. Smart People say that works fine in some climates. But here in the Pacific Northwest we swear by ventilated cavities.

This is particularly true when we’re building high performance structures. We’re making walls thicker, more airtight, and more thermally resistant, so suddenly we don’t have a bunch of air and heat passing through them like we used to. That’s a great thing for energy performance and comfort, but not for the drying capacity of walls. No matter how careful we are in detailing our walls and managing moisture in all its forms, we neglect drying capacity at our own – and our buildings’ – peril. We need to assume that walls will get wet and make sure they can dry well. Otherwise we’re tempting the gods of rot and building failure.

Ventilated rainscreens dramatically increase drying capacity. All that air moving across the face of a vapor-open WRB acts like a big fan, drawing moisture out of the wall assembly. The cladding loves it, too.

Ventilated=dry. And dry=happy.

Lest we get too happy with ourselves and our 21st century building innovations, the Romans knew about the virtues of ventilated wall cavities 2000 years ago. None other than Vitruvius wrote about them in his “Ten Books On Architecture.” We first learned about Vitruvius’ ventilated cavities during the keynote address by Mark R. Morden, Associate Principal at WJE, at AIA Seattle’s Building Envelope Forum last year. Joe Lstiburek cited Vitruvius again a couple weeks ago in his excellent “Vitruvius Does Veneers.”

Here are the quotes from the “Ten Books On Architecture” that Joe shared:

“…if a wall is in a state of dampness all over, construct a second thin wall a little way from it…at a distance suited to the circumstances…with vents to the open air…when the wall is brought up to the top, leave air holes there. For if the moisture has no means of getting out by vents at the bottom and at the top, it will not fail to spread all over the new wall.” (Book VII, Chapter IV)

“this we may learn from several monuments…in the course of time, the mortar has lost its strength…and so the monuments are tumbling down and going to pieces, with their joints loosened by the settling of the material that bound them together… He who wishes to avoid such a disaster should leave a cavity behind the facings, and on the inside build walls two feet thick, made of red dimension stone or burnt brick or lava in courses, and then bind them to the fronts by means of iron clamps and lead.” (Book II, Chapter VII)

Not to get carried away with the quotes from the classics, but “there is nothing new under the sun,” apparently. Vitruvius saw building failure in ancient Rome, and knew that ventilated cavities were a key way to avoid it.

So, in “minding the gap” in 2015, how big should the cavity be? While you can go smaller, our default at Hammer & Hand is ¾” or more, largely because we use 1×4 battens to create the gap. We’re always happy to go larger, and routinely do so, especially when we create crisscrossing battens for vertical siding conditions.

Rainscreen detail for vertical siding condition.

(An aside: the size of battens can be played with for architectural effect, allowing the designer to easily move the exterior plane of a building outward – to hide the housing for movable exterior shades, for example.)

The key is to make sure that you always have a gap of ¼” or more at the top and bottom of the cladding (including at punched openings) so that you’re always setting up the stack effect in the rainscreen cavity. And tell your subs to keep their caulk guns away from that gap! If it ain’t ventilated, it ain’t drying your wall.