Boston architectural firm’s series of sketches describes Passive House approach in an engaging and straightforward way.

Having spent three years in Boston myself (and, therefore, three frigid winters), I’m not surprised by the groundswell of interest and expertise in the Passive House standard there. If anyone can benefit from the thermal comfort and energy performance gains of Passive House, it’s New Englanders.

Last week, Jordan Goldman of Boston’s Zero-Energy Design was featured in an NPR interview about Passive House. This week, Skylar here at Hammer & Hand turned me on to these great illustrations by the Boston firm Albert, Righter and Tittman Architects. The images were created for their presentation “Getting to Passive House in Vermont & Redifining Affordable Housing”, but they are universally applicable. The illustrations help make the case that green building in the new millennium should be about simplicity: weaving together and maximizing simple technologies rather than relying on fancy gizmos and complex systems.

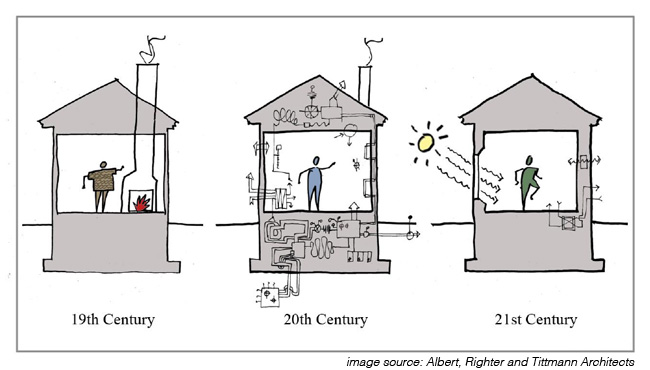

This first image encapsulates nicely the progression in building technology over the centuries, from wood-heated homes in the 19th century, to a complex tangle of building systems in 20th century homes, to the promise of simplicity presented by today’s Passive House standard:

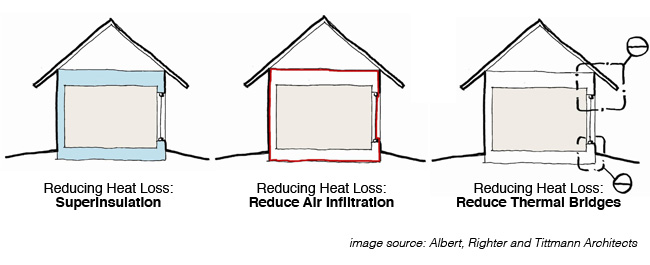

It’s all about the envelope. A fundamental principle of Passive House design is to reduce heat loss by superinsulating homes, creating airtight building envelopes, and eliminating thermal bridges (elements or penetrations that allow heat or cold to leak through the thermal envelope):

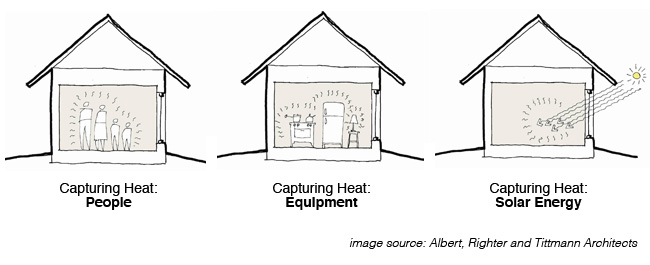

With a well-designed and executed building envelope in place, almost all the heating needs of a Passive House can be met by body heat, heat from lights and appliances, and solar gain:

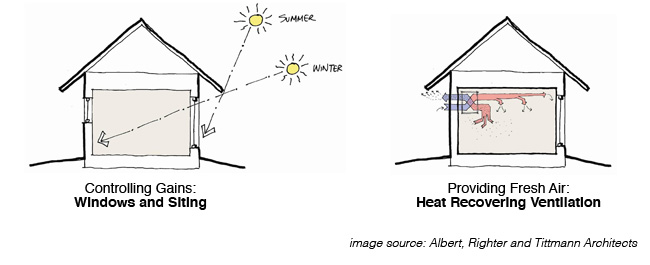

The control of these solar gains can be easily calibrated though a combination of old-fashioned siting (along the east-west axis), shade-providing overhangs for the summer months, and the careful placement of high-performance windows. All that’s left is to incorporate heat-recovering mechanical ventilation, a simple system that exhausts spent air and brings in fresh air, all the while capturing and retaining the thermal energy of that exhausted air:

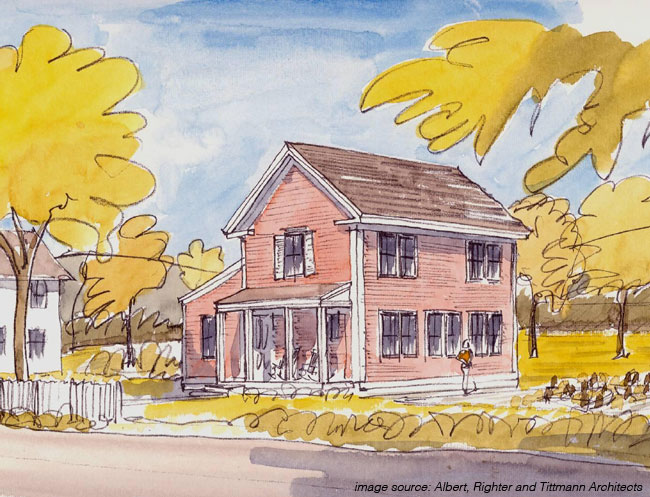

The end result is a comfortable, normal-looking home that saves 75-90% of the energy consumed by a conventional home. A case in point: Albert, Righter and Tittman Architects‘ Passive House in Vermont:

-Zack

Back to Field Notes