AIA Seattle continuing education session, co-hosted by Passive House Alliance US, grapples with the question.

On behalf of the Passive House Alliance US (PHAUS), Hammer & Hand’s Sam Hagerman moderated this Tuesday’s AIA Seattle “Deep Dive” continuing education intensive entitled “Passive House: High Performance, High Design,” presented to a standing-room-only crowd of architects in the basement of The Bullitt Center. (Thank you to AIA Seattle sustainability director Cassandra Delaune for inviting us to help craft the session and for all her work in presenting the event.)

Sam was joined by Joe Herrin of Heliotrope Architects, Jeffrey Stuhr and Cory Hawbecker of Holst Architecture, Skylar Swinford of Hammer & Hand, and Graham Irwin of Essential Habitat. The group tackled both how Passive House supports high performance green building and high design, and how Passive House complements the Living Building Challenge (LBC) by enabling projects to reach LBC’s “Energy Petal” (ie. net zero energy) through economy of means. See our post, “What’s the best path to net zero energy buildings?” for more on this perspective.

It was a great session and we felt honored to be joined by a group of heavy hitters. The complementary relationships between high performance building and high design, and Passive House and Living Building Challenge, were well-told and documented through real projects, in the ground.

But our good friend, colleague, and kindred spirit Graham Irwin (Essential Habitat) didn’t entirely play along. In fact, he presented a critique of net zero energy building – a critique that warrants some attention here.

Net zero energy (or NZE) relies on both conservation (energy efficiency) and production (onsite renewable energy) to reach its balance of energy-consumed and energy-produced: “net zero.” In our view, the best route to NZE is through conservation first and production second. And Passive House, with its revolutionary energy efficiency is the place to start.

But Graham points out that NZE pits conservation against production. And he’s right. By definition NZE is a zero sum game. The more efficient you make a building the less onsite renewable energy you have to produce to reach zero. And vice versa.

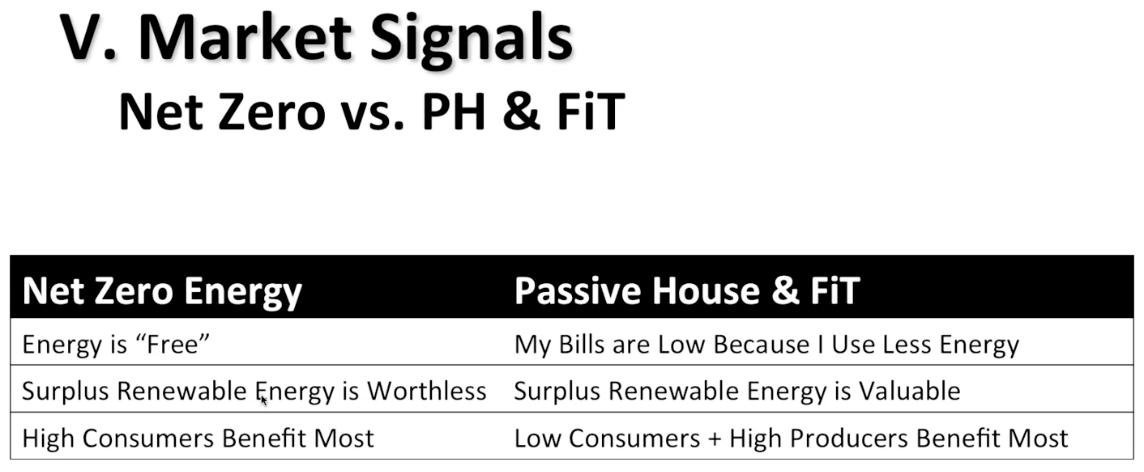

Graham argues that rather than pitting the two social goods of efficiency and renewables against one another, we should align them to run in parallel: first, pursue Passive House to build the best, most efficient building possible; second, reward renewable energy production with a feed-in tariff system that pays building owners for the surplus energy they supply back to the grid. Why stop at net zero? Why not become net positive and reap the financial rewards for becoming an energy producer? Of course, this raises some political questions involving the turf owned by big utilities, but that’s a topic for another day. (Worth noting: the Karuna House’s surplus energy is currently sold back to the grid through a State of Oregon feed-in tariff program.)

Graham summarized his arguments for the pros of the Passive House/feed-in tariff route and the cons of NZE in this chart:

Chart by Graham Irwin, Essential Habitat

Graham also challenged NZE’s emphasis on onsite renewable production. Citing The Bullitt Center (a project that he admires) as an example, he posed the question: why not move the building’s solar array away from gray Seattle and to the sunny American Southwest?

Good points.

But as is so often the case in solution-making around tough challenges like carbon neutrality for buildings, the answer isn’t “either, or” but rather “yes, and.”

We’d be the first to agree that Passive House plus feed-in tariff (ie. energy conservation plus incentivized renewable energy production) makes perfect sense. Hopefully public policy makers will make feed-in tariff programs ubiquitous and lasting. But today they are not.

Likewise, some system of rewarding building owners for investments in remote renewable energy production (a la the solar PV arrays in the American Southwest that could “power” another version of The Bullitt Center) makes sense.

But in the meantime, net zero energy remains an empowering and accessible goal for building owners. Like Passive House, it’s an easy to understand green building target, something measurable to shoot for. It’s also a step toward carbon neutrality that individuals can take now without waiting for legislators to make big policy changes around feed-in tariff or other incentives. (Maybe it’s the individualism embodied in this second point that has helped NZE capture the imagination of so many über-green Americans.)

So yes, let’s pursue feed-in tariff programs and large-scale district solar schemes. But in the meantime, why not support the “get ‘er done” spirit of net zero energy projects when they’re powered by a conservation-first approach like Passive House?

After all, we’ll be building a bunch of great high performance buildings along the way. And if we build them solar-ready, those renewables-rewarded-by-feed-in-tariff can come along later.

“Yes, and.”

NOTE: We recently published a series of posts giving an updated view of Zero Energy building and it’s relationship with the high performance building approach of Passive House. Here they are:

“Is Solar Smart: Reaching Net Zero, Part I”

“Performance Matters: Reaching Net Zero, Part II“

“Legacy Building: Reaching Net Zero, Part III”