As fine home building aficionados, we’re always looking for ways to indulge our zeal for working with wood.

The other day I sat down with Hammer and Hand project managers M.A.C. Casares and Christopher “Coop” Cooper to reminisce about a home building project that stands out in the annals of past H&H jobs as a singular celebration of wood and craft, or as M.A.C. and Coop described it, a “woodworkers’ cathedral”.

Designed by Emerick Architects and built by Hammer and Hand for wine aficionado clients and their young family, the Arts and Crafts revival sits on 40 acres of land nestled among the vineyards of Yamhill County. The new home project garnered lots of press attention, and deservedly so, including a 2002 Oregon Home feature article that enthused: “the carpenters and other crew members eagerly rose to the challenge of achieving a level of craftsmanship worthy of fine furniture making, if not violin making.”

The project was a major undertaking, but became a labor of love for our crew. Here’s our own Daniel Thomas as quoted by Oregon Home: “Once the crew got out there and understood the level of quality that was expected of them, they really took possession of it, the way craftsmen will do. They held that job in such high esteem that nothing but perfection was going to be allowed to get nailed up on the wall.”

To run the job, M.A.C. ended up moving out to Yamhill for two years. “It was a life changer, a really once-in-a-lifetime job,” M.A.C. told me. “The level of carpentry and detail was phenomenal. You could be working on the same wall or ceiling for a month. It was awesome.”

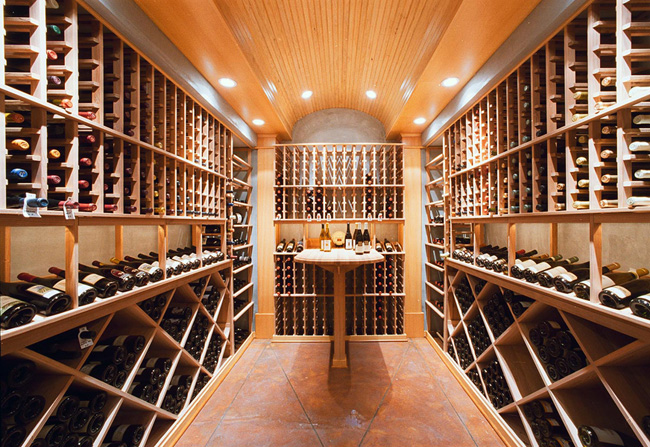

During our conversation, Coop and M.A.C. walked me through the project, starting (appropriately enough given the owners’ strong affinity for wine) with the wine cellar.

Originally meant to be a simple storage room, this barrel vaulted cellar was designed on the fly (an on-the-ground example of how effective design-build-client collaboration and improvisation can be). Coop built the vault from tongue and groove fir. The clay-based stucco on the walls is the same material that wraps the house, making a subtle inside/outside connection. And the cellar was wired with full data hookups for cataloging wines online (a big deal in 2002 … remember the days before wifi?).

Moving upstairs to the main floor, you can see the incredible woodworking and detailing at play in the house. The crown consists of huge cove pieces of wood with an 8″ stand. With the except of the crown, the tongue and groove, and the flooring, all wood was shaped on site. The fir came in on a semi truck and was examined, with knotty pieces sent back to the lumber yard. Only one knot exists in the whole house … one knot in one joint!

The tongue and groove ceiling material in this shot took 2 guys 5 weeks to install, because all the lines had to line up perfectly. The column capitals have 3×3″ brass inlays, a traditional touch for higher end Craftsman homes. “This house is as traditional as you can get and still be built in this day and age,” M.A.C. said.

Here we get a glimpse of the bathroom with its green marble vanities and floors. The French doors open onto an outdoor living room.

Here’s the anteroom, the most technically difficult room of the house in terms of aligning the wood. All the arches were hand-cut on site. The crew worked on a scaffold on wheels, with one carpenter on the ground measuring and cutting pieces and another on the scaffold installing the wood. “It’s the closest thing I’ve ever been to building the Sistine Chapel,” said Coop. “It was like being in a church. If you love wood and love woodworking, it doesn’t get any better than this.”

Here we see the living room in the foreground, with the gallery hallway in the center, and the kitchen beyond. “The gallery is really important for the design,” M.A.C. told me. “It’s a conduit for the rest of the house.” A coffered tongue and groove ceiling graces the entire gallery, with arched box beams defining “bays” that create portals to the spaces off of the gallery. The arched box beams were a technical challenge, with all work milled on site.

Of the master bedroom M.A.C. said: “somebody walked in and said, ‘Oh look, someone took a boat and turned it upside down!'” The collar ties and king posts tie it all together, and the arch of the collar ties is restated above the double doors. No trim meant no room for error. Coop added, “Neil Cooper and I took 3 months on this room.”

On the top right hand corner of the image a dutch hip finishes the gable. Notice how all the lines in the tongue and groove match perfectly. Cool, no?

In this kids’ bedroom we see more tongue and groove arch work, this time over the window. Those window screens were designed by M.A.C. (“after going to a Mondrian exhibit” quipped Coop). And see the little round holes in the ceiling, one above each window? That’s the high pressure HVAC system – low profile for low visual impact.

The kitchen features died concrete counter tops. A floating shelf runs all the way around, bolted through. This was another room that required lots of careful alignment work.

The left image above shows the inglenook. The tongue and groove pieces on either side of the fireplace was created from the leftover pieces of other rooms in the house.

The right image is a great shot showing how the gallery functions, with its coffers and portals to adjoining spaces. It also hints at how the details of one room connect with all other spaces … the trim at the bottom of the capitals meets the plate rail trim of the kitchen and other adjacent rooms.

The dining room on the left is reminiscent of the master bedroom, complete with dutch hip. The plate rail serves as the head case to the windows, buffet and doors. That cool red lamp was hand painted in San Francisco. All vents in the wood ceiling were custom-made from wood on site.

The detail of the inglenook on the right shows its masonry wood burning firebox, as well as the benches that double as linen storage for the home.

On the left we see the breakfast nook, whose ceiling pitch was added to suggest an Old World craftsman look.

The main entry on the right boasts another bench that doubles as linen storage, while the arch theme is repeated above the bench. A clever drop box for mail (across from the bench) acts like a laundry chute, shuttling mail from the front door entry into the “command center”, a bill-organizing-and-paying nook in the adjacent kitchen.

Throughout the house, nothing terminates out in to space. Instead, it all ties in and continues, connecting room to gallery to entry back to room, and so on. The overall effect is that of the Renaissance ideal of design – you can’t take anything away without diminishing the whole. It all works as a cohesive unit.

Now there’s no question that the home took a lot of wood to build. As M.A.C. says, “this is the largest amount of unpainted wood I’ve ever seen in a house.” Nevertheless, a green sensibility was brought to the project. All of the cherry flooring was certified sustainable, the house collects rainwater to use for irrigating the garden and grounds, a geothermal heat pump facilitates energy efficiency, and the original 90-year-old barn was upcycled to serve as the garage.

The project was a deeply satisfying collaboration with clients and architect. “Because of the Emericks’ vision, all of the cabinetry, casework and finish carpentry meld into one seamless whole of the highest level of finish work”, says Daniel.

-Zack

Back to Field Notes